The NY Fed on the Consequences of Extend and Pretend

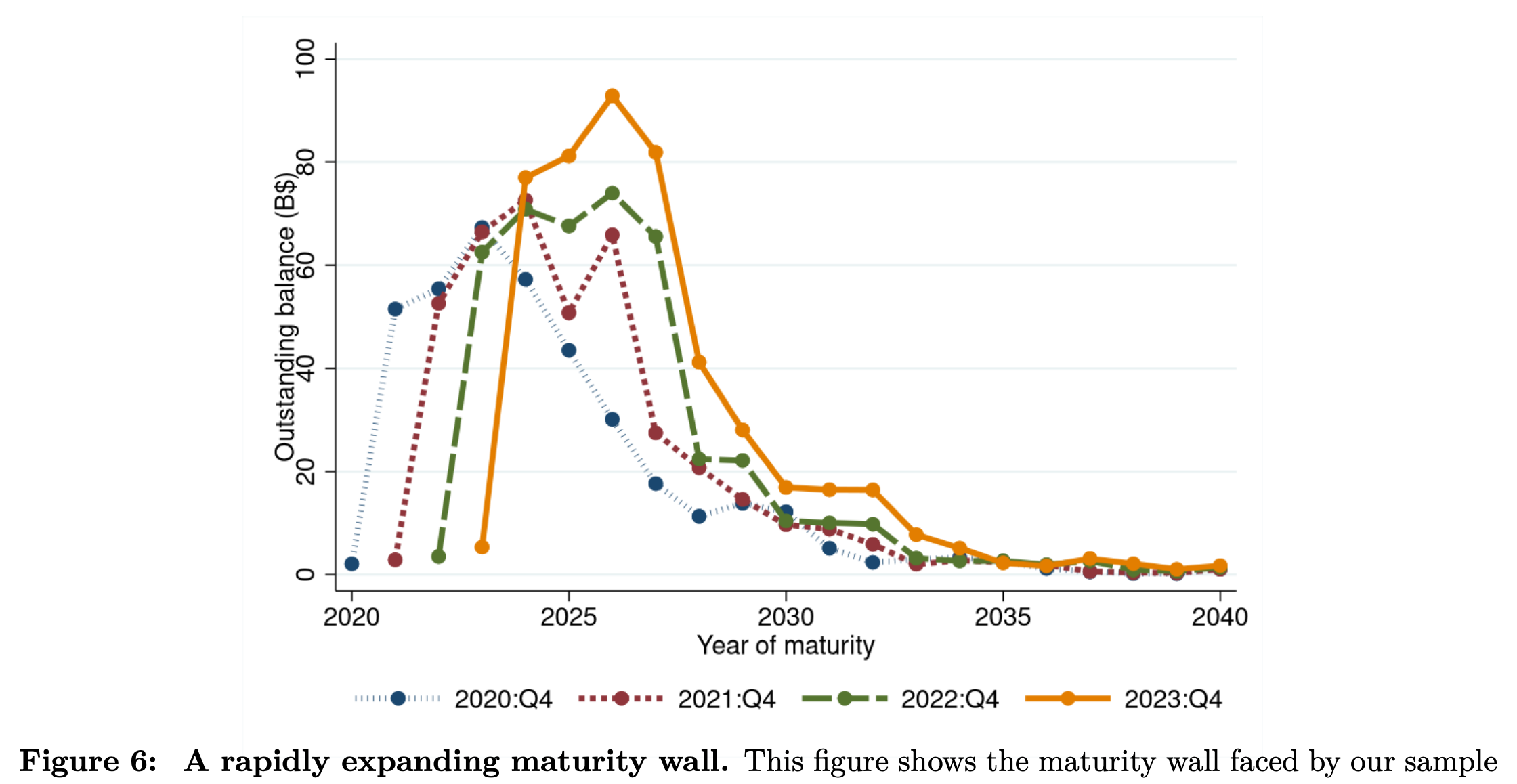

Quick highlight from the NY Fed’s report on extend and pretend: There’s a (new) wall of CRE loan maturities set to expire in 2026.

How does this compare to the wall of loan maturities that were expected last year but didn’t have that big of an impact? If they extended-and-pretended last year’s loan maturities, can’t they just do it again in 2026? This report doesn’t have a forceful answer to those questions, but there’s compelling evidence here that shows the circumstances that give rise to extend and pretend practices and some of the effects of these practices on the lending market.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York: “Extend and Pretend in the U.S. CRE Market”

It may not be earth-shattering news to report on the extend and pretend tactics that were so frequently discussed these past 2 years, but the idea that CRE borrowers (and lenders) could ignore unrealized losses and just wait until rates and prices improve, there’s got to be a cost to that. The NY Fed’s recent report suggests that extend and pretend won’t let borrowers and lenders escape their financial reckoning.

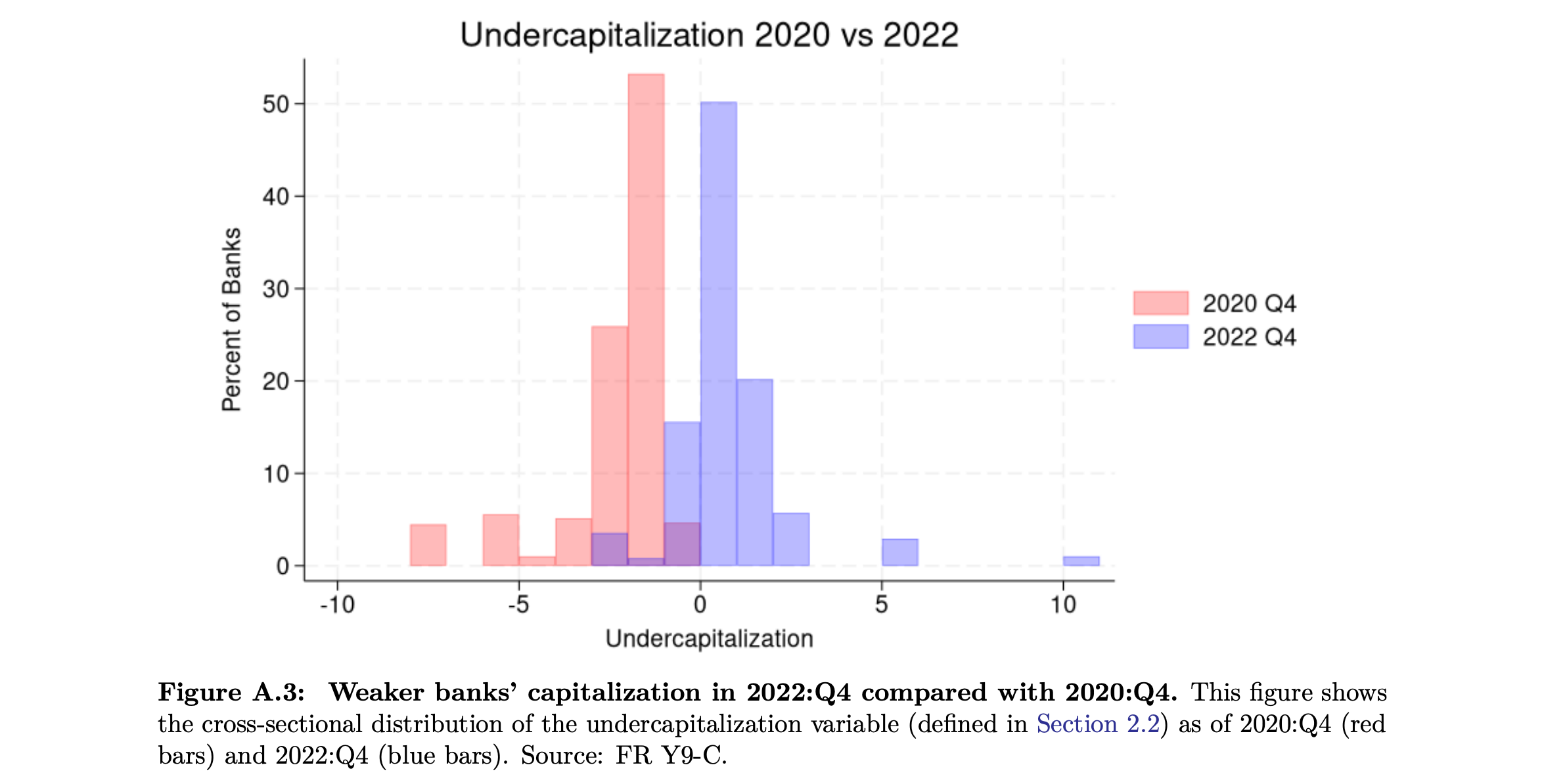

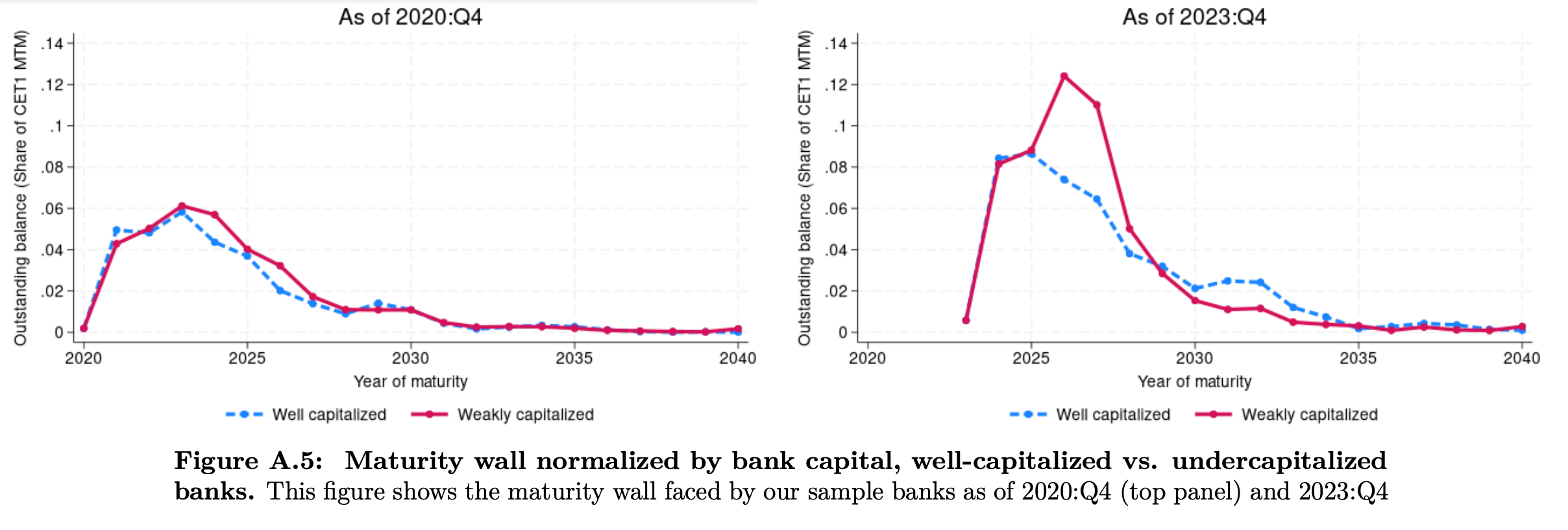

The “conceptual framework” of the report “centers on banks’ incentives to extend the maturity of their existing impaired loans to avoid writing off their capital. This incentive is particularly pronounced from 2022:Q1 onward as rapidly rising rates created large marked-to-market losses on securities held by banks, eroding their economic capital.”

They’ve got 5 parts for their analysis:

1. “[C]redit risk in the CRE market has substantially increased in the post-pandemic period but banks—weakly capitalized ones in particular—have been sluggish in assessing the associated losses.” This first point reminds me of the accounts of CRE mortgage broker conferences during the run-up in interest rates. CRE prices had taken a hit and were months if not years away from a recovery, but the mood among mortgage brokers was relatively calm. That’s not wholly unexpected (I don’t imagine that bankers are a flighty or reactionary bunch), but given that weakly-capitalized banks were the leaders in this sluggishness, I think this slow reaction is far less the result of blasé attitudes than disappointing balance sheets. This report doesn’t exactly pull back the curtain on banks or bankers’ individual decisions as much as it tracks a widespread process in which, for instance, “the same borrower is assigned a systematically lower probability of default by an undercapitalized bank compared to a well capitalized bank.”

2. “[U]ndercapitalized banks disproportionately extend the maturities of these distressed loans and understate their default probabilities, leading to fewer realized defaults.”

3. “[A] loan to a CRE REIT that has experienced a large valuation decline is assigned a lower probability of default if granted by a weakly capitalized bank compared to a better capitalized one.”

4. [T]he maturity extensions granted by weakly capitalized banks to distressed borrowers result in reduced credit origination in both CRE mortgage credit and C&I credit to firms.

5. “[B]anks’ extend-and-pretend has led to an ever-expanding ‘maturity wall’, namely a rapidly increasing volume of CRE loans set to mature in the near term . . . [driven by] weakly capitalized banks.”

The damages of this “credit misallocation” associated with this extend and pretend approach “might slow down the capital reallocation needed to sustain the transition of real estate markets to the post-pandemic equilibrium” and “exposes banks . . . to sudden large losses which can be exacerbated by fire sales dynamics and bankruptcy courts congestion.”

They use office-to-residential conversions as an example of a transition into post-pandemic equilibrium, which I’m not too bullish on even absent this extend and pretend dynamic, but the report does show evidence that extend and pretend practices resulted in fewer CRE loan originations. That second part, the exposure to sudden large losses, could motivate CRE lenders to phase out the extensions and pretensions.

I remember last year when the Federal Reserve issued guidance that encouraged CRE lenders to work out and accommodate lenders hit by declining property prices and increasing interest rates. Interest rates are just as high as they were when that guidance was issued, but to be fair, rates were headed up last year and are headed down (let’s hope) right now.

Is it fair to think that the NY Fed’s attention on the negative effects of extend and pretend is motivated by an assumption that banks/lenders and CRE borrowers are/will be in better shape than they were in 2023, that maybe the CRE market and financial markets can handle these loan maturities now and in the future without a crisis? Extend and pretend practices are not the exact same as the kind of accommodations and workouts described in the U.S. Fed’s guidelines in 2023, but they’re not far off:

“Loan workout arrangements can take many forms, including, but not limited to:

• Renewing or extending loan terms;

• Granting additional credit to improve prospects for overall repayment; or

• Restructuring”

Returning to the topic of this new wall of loan maturities, would I be so off base if I thought that this wall won’t be quite as dramatic as it looks? We tracked a similar wall of loan maturities that did not produce a great deal of CRE distress and buying opportunities in October of 2023. Likely some of these maturities were extended and accommodated, but the lack real drama in the market last year makes me more skeptical that a subsequent wave of loan maturities have a major effect. Could it be the case where, if many of these loans maturing have already been extended, that we could actually see the opportunities for distressed sales for CRE buyers? Maybe, but this upcoming wave has a key difference from last year.

The interest rate environment for these upcoming loan maturities is going to be completely different from October 2023. CRE price trends could also be kind to borrowers, and maybe a deal that was once underwater will be upright and above the waterline. These changed conditions could blunt the force of this wall of loan maturities, but the New York Fed didn’t write this paper for nothing.