Housing Proposals from the Harris Campaign

The White House: “Remarks by Vice President Harris at a Campaign Event in Raleigh, NC” [focusing on the economy and touching on housing and rents] – https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2024/08/16/remarks-by-vice-president-harris-at-a-campaign-event-in-raleigh-nc/

- Additional reading:

- The Atlantic: “We’re Entering an AI Price-Fixing Dystopia”

- Curbed (New York Magazine): “A Housing Expert on Kamala Harris’s New Proposals”

- The White House: “Biden-Harris Administration Takes New Actions to Lower Housing Costs by Cutting Red Tape to Build More Housing” (August 2024)

- Ballotopedia: “California Proposition 33, Prohibit State Limitations on Local Rent Control Initiative (2024)”

- City and County of San Francisco: “SF Board of Supervisors Passes First-in-the-Nation Local Ban on Rent Price Fixing”

- Peter Welch (US Senator from Vermont): “Welch and Wyden Introduce Legislation to Crack Down on Companies that Inflate Rents with Price-Fixing Algorithms”

I marshaled a short list of materials to provide a more detailed account of housing policy discussions connected to the Kamala Harris campaign. Amplified by Kamala’s recent remarks at a campaign event in Raleigh, NC, the Democratic National Convention began less than a week later and kept the attention on these housing issues, even though it is sometimes difficult to get a specific sense of what’s being planned.

In a non-housing example, there was some news earlier this week that Harris’ allies may be walking back, or, let’s say “clarifying” her remarks in NC about combating price gouging. If you’re skeptical of some of these policies, you might interpret this clarification as a sign that the more extreme end of these ideas is not going to happen.

Harris’s comments in Raleigh, NC were announced as referenced a few general ideas, and like I mentioned earlier, she didn’t give specific details in the remarks themselves, but there are a few documents, several from the Biden White House, one from a Senate bill proposed earlier this year, and a couple pieces of legislation from California, that could fill in some of these gaps. I’m not saying that this is what the Harris housing policy is going to look like, but it does offer a model for what it might be.

Noted her history working on a homeowner bill of rights and fighting predatory lending, and she later mentions that her “administration will provide first-time homebuyers with $25,000 to help with the down payment on a new home”

Reminder: we’re not getting specific policies yet. To be honest, there’s some benefit in not laying out the specific mechanisms and explanations of where the money’s coming from and how it’s being distributed.

She also talked about increasing housing supply: Cutting down red tape, and “building 3 million new homes and rentals that are affordable for the middle class”

Very cool and perhaps the most do-able of the ideas here, given its bipartisan appeal, but I wonder about the specifics of this 3 million number.

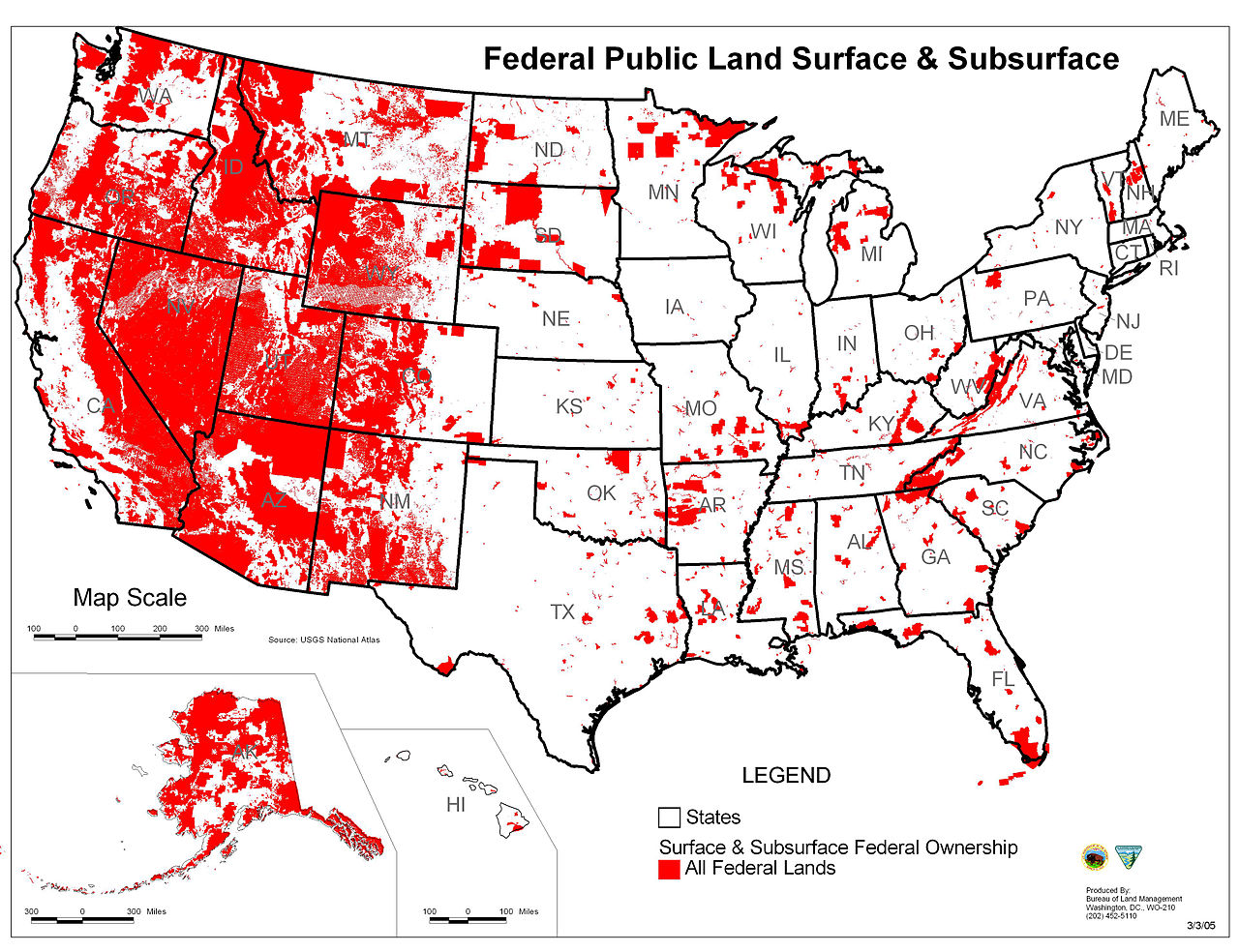

Earlier this year, the Biden-Harris administration put out a statement that mentioned “[r]epurposing public land sustainably to enable as many as 15,000 additional affordable housing units to be built in Nevada,” but the concrete example was a project that involves 300 units. I’m not saying that the 3 million or 15,000 unit number is impossible or anything, but I couldn’t find real-world examples of projects that get us meaningfully close to the number

I understand that the 300-unit project is kindof a proof-of-concept example, but if one of the ideas being floated in these housing discussions is the idea of turning federal land over to be residential housing, I do wonder where that federal land is. There’s a whole lot of it in the West, but how close is this land to major cities, towns, or employers? I don’t want to throw cold water on this idea either, I really am curious about how much housing one could get out of opening up more federal land.

It’s worth nothing that this earlier statement from the Biden-Harris administration is just one part of a paper trail of statements and announcements that track the current administration’s efforts and stance on housing, three of which were released this year. These White House statements are an effective tool for determining the shape of housing policies of a potential Kamala Harris administration. Interestingly, the most recent of these statements, from August 13, does not include criticism of “corporate landlords,” but a July statement from the White House does, and in Harris’s comments in NC, she brings this landlord critique up specifically:

“Because, you know, some corporate landlords — some of them buy dozens, if not hundreds, of houses and apartments. Then they turn them around and rent them out at extremely high prices, and it can make it impossible, then, for regular people to be able to buy or even rent a home.

Some corporate landlords collude with each other to set artificially high rental prices, often using algorithms and price-fixing software to do it. It’s anticompetitive, and it drives up costs. I will fight for a law that cracks down on these practices.”

So, we’ve got two ideas here: In the first paragraph, a critique of corporate landlords.

There’s an out here, because she says “some” corporate landlords, and I’ll leave it up to the corporate landlords themselves to see if they’re the ones Harris is talking about who are hiking up rents and making it impossible for people to afford a home.

That being said, Harris’s description of people who buy “dozens, if not hundreds” of apartments is setting the bar about a thousand times lower than reality.

Is it about the number of apartments owned by a single entity?

This is mentioned in the July 2024 Biden White House housing announcement, (not the August 2024 one, which is more about housing supply increases)

The second paragraph gets at the kinds of actions that the Harris campaign is looking to address from these corporate landlords. They “collude with each other . . . often using algorithms and price-fixing software.”

This is the jumping-off point for a lot of the accompanying material I’ve found here, the efforts to curb the use of software that landlords use to suggest the best rents to set for their apartments.

We have talked about this before, and I don’t want to just completely re-hash the same conversation, but yeah, we didn’t think it was a great idea, and we can get into here if needed.

So what can we use as a guide that can flesh out these two little paragraphs on corporate landlords and price-fixing software?

Well, the Biden-Harris administration has put out several housing-related announcements/proposals on the White House letterhead, and while the earlier proposals were almost solely focused on the “carrot” of increasing housing supply through lower regulations and positive incentives, the more recent announcements in 2024 have more of a “stick” approach intended to prevent landlords from keeping rents too high.

The text of this “Fact Sheet” from the White House does mention “pending litigation for . . . alleged use of proprietary algorithms to raise rents on tenants,” but does not suggest a specific policy. The mention alone, though, makes it clear that this is a focus of the White House.

The more detailed proposal here connects with that paragraph in Harris’s NC speech where she calls out “corporate landlords.”

In this Biden-Harris White House fact sheet, corporate landlords are defined as any company or entity that owns more than 50 apartment units. And the document proposes that these corporate landlords should be punished for raising rents above 5% by removing their accelerated depreciation tax benefits.

I have not yet heard news of any legislation in progress that would move this proposal forward, but when Harris mentions “corporate landlords,” this is the discourse, these 2024 statements from the White House, is the space within which she is operating.

Harris’s NC remarks reference “a law [emphasis mine] that cracks down on these practices” what kind of legislation is Harris talking about?

There are ongoing cases against RealPage happening in the courtroom, [Note: The Justice Department has since sued RealPage] for but what about the legislature?

A Senate bill proposed in January of this year is a pretty good candidate!

According to a press release from VT Sen. Peter Welch who helped introduce the bill,

“Specifically, the bill would:

Make it unlawful for rental property owners to contract for the services of a company that coordinates rental housing prices and supply information, and designate such arrangements a per se violation of the Sherman Act;

Prohibit the practice of coordinating price, supply, and other rental housing information among two or more rental property owners;

Make it unlawful for two or more coordinators to merge where a merger creates an appreciable risk of materially lessening competition; and

Allow individual plaintiffs to invalidate any pre-dispute arbitration agreement or pre-dispute joint action waiver that would prevent their bringing a suit under this act.”

The bill itself is quite short, and its definition of the kinds of prohibited acts includes any company/software that takes rental data from more than 2 apartment owners, “uses computation” to process that data, and suggests rent prices based on that computation.

This is about as wide of a net as you can cast, and it would entangle just about every company that offers a software service that advises on apartment leasing prices. All you need is data from 2 or more apartment owners, and a little bit of computation.

To be fair, the bill is likely worded that broadly to avoid loopholes and workarounds, but the breadth of this specific wording, it does make me think about what if this kind of law had even more breadth and expanded not just to apartment rents but to other prices.

A recent article in The Atlantic is an excellent and relatively brief contribution to this conversation about using software to set prices (or fix them, or collude, or what-have-you).

The title of the article is “We’re Entering an AI Price-Fixing Dystopia,” and its main focus is on the so-called rent price-fixing software.

It sketches out a decent outline of the issue, but I did have one sticking point in the story that I think is really pivotal to this whole issue.

“RealPage thus makes it hard for customers to override its recommendations, according to the lawsuits, allegedly even requiring a written justification and explicit approval from RealPage staff. Former employees have said that failure to comply with the company’s recommendations could result in clients being kicked off the service. ‘This, to me, is the biggest giveaway,’ Lee Hepner, an antitrust lawyer at the American Economic Liberties Project, an anti-monopoly organization, told me. ‘Enforced compliance is the hallmark feature of any cartel.’”

I have spoken with people who use RealPage, including our brilliant and excellent, Katrina Greene, host of the property management podcast The Complex, who would push back against the idea that someone using RealPage would be punished for not adhering to its recommendations.

In our earlier discussions of the issue of rental pricing services like RealPage, I summarized the case against them as this idea of a landlord mindlessly agreeing to whatever the suggestion is from RealPage.

I don’t have Katrina Greene’s experience, but I do wonder if, in response to this increased scrutiny, RealPage programs in some disclaimers and pop-ups that make it clear to landlords that they can and should make their own independent decisions on rental prices, and any deviation from RealPage suggestions will not be punished in any way.

But there are other moments in this Atlantic article, the most interesting of which is when the author expands beyond rental housing, citing a recent study of German gas stations:

“[W]hen one major player adopted a pricing algorithm, its margins didn’t budge, but when two major players adopted different pricing algorithms, the margins for both increased by 38 percent. ‘In situations like these, the algorithms themselves actually learn to collude with each other,’ Stucke told me. ‘That could make it possible to fix prices at a scale that we’ve never seen.’”

There is almost an air of inevitability in this account. Of course gas stations are using “computation” to figure out the best prices, and the fact that the algorithms fell into sync with each other is definitely chilling. But gas stations, okay. Apartments, okay. Would it be any surprise if we learned that corn farmers or steel foundries or lumber also use algorithms, computation, and data from more than two different companies to figure out how to set prices?

Reading this Atlantic article, I came away with the thought that, in order for these efforts to ban apartment rent software to make sense, you need to consider housing as something separate from the other kinds of products and services that utilize software and computation to set the best price.

There’s also Proposition 33, which is up for a vote in California and would get rid of the rent control ban in the state, which is related but not as specific to this issue of algorithmic price fixing.

More interesting, though, is a recently-passed San Francisco ordinance that bans “both the sale and use of software which combines non-public competitor data to set, recommend or advise on rents and occupancy levels.”

If the sticking point is using non-public data, would it be legal if the rent software company publicly lists the data it uses? Yeah, it might be a bummer for a software company to publicly list the dataset, but it’s the algorithm, the crunching of the numbers, that’s getting the results, right? Or maybe the “non-public competitor data” includes the specific methodology behind the rent setting software.